Travel choices

People make a large amount of choices each day with respect to when, how, when and where they travel. The same holds true for pedestrians. They also continuously determine where to walk, when to walk, which route to take, and how

they move (fast, slow, aggressive, alert, etc.). If one can alter the choices that people make, one can alter the future. Therefore, understanding pedestrian choice behaviour is essential to develop effective crowd management.

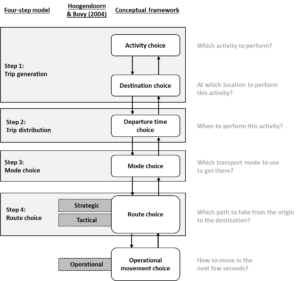

The travel choice behaviour has been extensively studied. Most studies identify and quantify the travel choice behaviour in order to forecast transportation demand under alternative future scenarios. The most common models for generating the demand forecast are the trip-based models (`four-step’ model) and activity-based models. These demand forecast models simulate a number of distinct travel choices, among others activity choice, destination choice, mode choice and route choice.

Next to these four travel choices, there are strong indications that the route choice behaviour of pedestrians is influenced by more specific details of the infrastructure, such as the number of left hand turns and the gradient of the road (e.g. Borst, 2009; Buehler et al., 2016). Moreover, pedestrians have additional degrees of movement freedom (i.e. other trip-chaining possibilities and different usage of the infrastructure) and are influenced differently by the physiological environment and the duration of a trip (e.g. fatigue) in comparison to private car and public transport travellers.

Pedestrian modelling research divides route choice into three sub-dimensions, namely strategic, tactical and operational choices (Hoogendoorn and Bovy, 2004). Here, the strategic route choice features the entire route from origin to destination and details the strategy of a pedestrian within a road network, while the tactical route choice identifies the strategy of pedestrians within complex parts of the infrastructure. The operational decisions feature their movement decisions for the next few seconds.

Figure 1 illustrates how these six travel choice dimensions can be conceptualized within one theoretical framework. Please note that the choices at different dimensions are related but a hierarchy between the choices does not necessarily exist. Moreover, at each consecutive choice dimension becomes more specific.

Figure 3.1. Conceptual framework of (pedestrians) travel choice behaviour.

ASSIGNMENT 1 – YOUR CHOICE BEHAVIOUR

For your trip from home to work, record the result of each choice level.

A. Activity choice

B. Destination choice

C. Departure time choice

D. Mode choice

E. Route choice

F. Operational movement choice (speed, direction)

Assignment 2 – changing travel choice behaviour

Identify for each of the 6 travel choices, what you could do to invite people to change their choice.

A. Activity choice

B. Destination choice

C. Departure time choice

D. Mode choice

E. Route choice

F. Operational movement choice (speed, direction)

info@cityflows-projects.eu

Stevinweg 1, Delft, The Netherlands